Celestine Moussa, 50, holds Abdel Latif, 2, as she turns away from the camera to protect her identity. Moussa was born Christian but converted to Islam when she married her high school sweetheart, Adawai Moussa, in 1986. It was different then, she said. “We lived in harmony. I even advised my sisters to marry a Muslim, because they are good people who take care of their wives.” Now she lies awake at night listening to gunfire. She rarely ventures beyond her gates. Her husband fled to neighboring Chad months earlier with the couple’s six children. She stayed behind to be close to her aging parents. She is also taking care of Abdel Latif, pictured, her husband’s son by his second wife, who left with him to Chad. They planned on a short separation. Now she’s afraid she might never see her husband and children again. “All I want is reconciliation between Muslims and Christians,” she said, wiping away tears. “ I just want things to be the way they were before.”

Ahmat Moussa, 45, holds pictures of his brothers, Mahamat Nourene, left, and Saleh Ahmat, who were killed when they tried to leave the country. They had tickets to fly to Chad on but when they arrived at the airport with three friends, they were told that the flight was overbooked. Family members pleaded with them to stay at the airport, where there was a camp for Muslims waiting to evacuate. But the men assured them they could get home safely. Not far from the airport gates, attackers armed with knives and stones surrounded the pair’s vehicle and killed them along with a traveling companion. Moussa wasn’t planning to leave Bangui, where the family owns houses and shops. But now he is selling. “Everyone is afraid,” he said.

“I am ready to kill,” Younus Yamsa, 43, said. Once he was the head of a large family, with an expensive house and hundreds of cows. Now, many of his relatives are dead or missing; their house is destroyed and their cattle slaughtered. He said he tried to defend them with his bow and arrows. But the attackers had guns. They cut off his mother’s head, he said, and burned his wife and two of his children to death in their home. He packed a bag of clothes and cooking pots to sell for money to transport the survivors out of the country. But the market was attacked with grenades. Yamsa was injured in both legs. He can’t walk without crutches. “If God gives me the opportunity to get revenge, I will take it,” he said. “Otherwise, I will tell the story to my children so they can avenge us.”

Habiba Hassan, 7, pulls up her skirt to reveal a long, pink scar running down her leg. “Please take me to my father, so I can drink milk,” she pleads, over and over. Food is scarce in PK 12, a neighborhood where she and her grandmother were sheltering with other survivors, most of them widows and children. Yerima said the girl’s parents escaped to Chad. Others in PK12 said they and five of their children were killed in the attack.

Adouje Ndjobo, 75, didn’t understand what he was doing in PK 12 but passed the time worrying about the family’s cows. His son left with them when militia fighters started attacking ethnic Peul - Muslim nomadic herders - and their cattle. Neighbors said Ndjobo’s four children were killed in the town of Bouali. “He was brought here all alone,” said Ibrahim Alawad, a lawyer and the community’s effective leader. “We try to take care of him. But I myself don’t know if we can help him.”

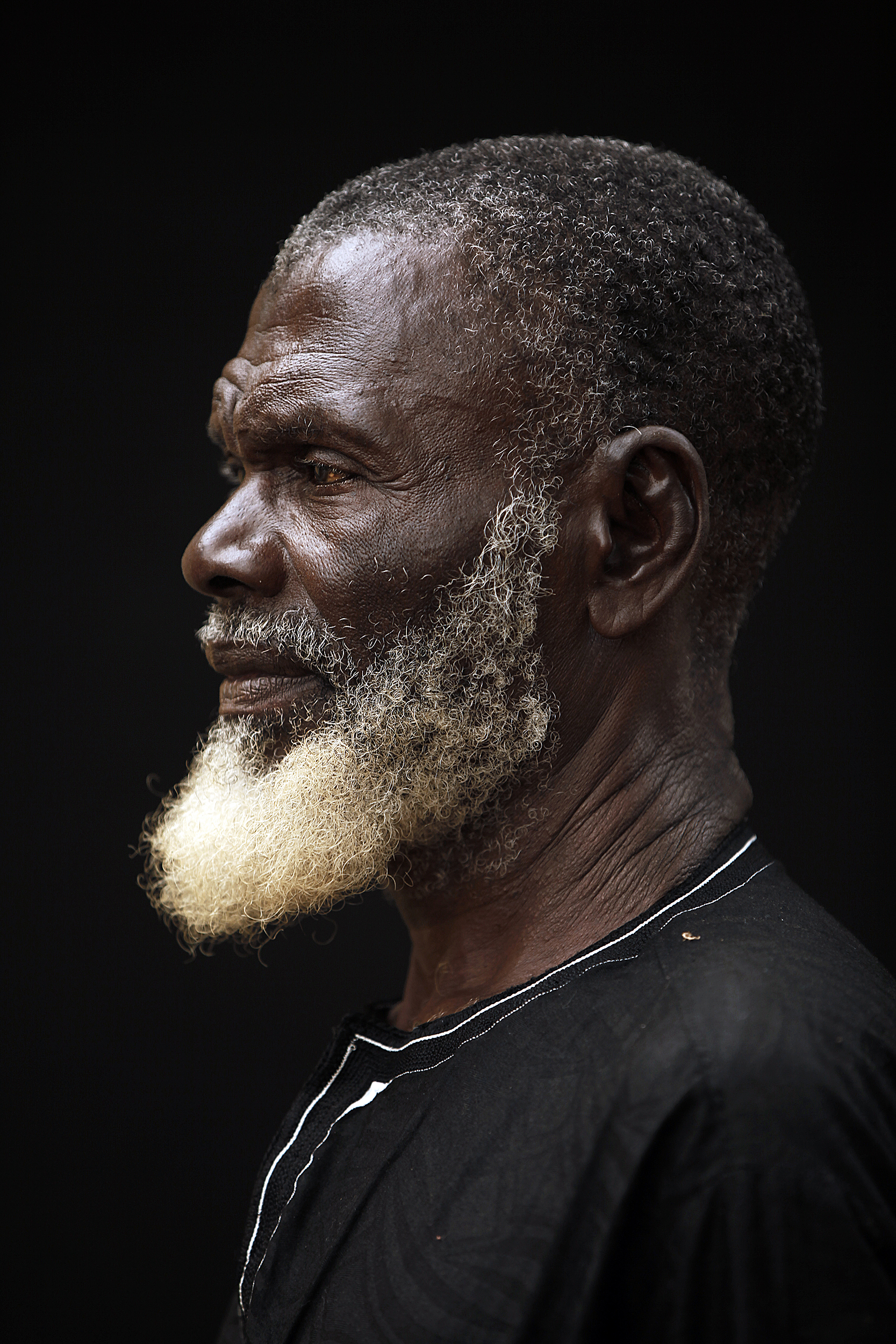

Sheik Daoud Muslim Mbokani, who said he's over 60, blames France for the increased violence against Muslims. When the former colonial ruler sent troops to help stabilize the country, they began by disarming the Muslim-dominated Seleka members. “Now people are killing Muslims,” said Mbokani, an Islamic community leader since the 1970s. “We are obliged to leave, and we don’t know where we should go.”

When Seleka forces pulled out of the western town of Bossembele, most of the Muslim population fled with them. But there weren’t enough vehicles. Aissatou Yerima, who says she's over 60, and her 7-year-old granddaughter, Habiba Hassan, joined about 100 people sheltering at the central mosque. The next morning, militiamen stormed the building. Those who could, fled into the forest. But Yerima had an injured leg. “I just closed my eyes and pretended to be dead,” she said. Habiba was shot in the leg. “She was crying, grandma, grandma, it hurts, it hurts,” Yerima said. She doesn’t know why the fighters didn’t kill them, as they did many people that day. Foreign aid workers found the pair among the bodies and brought them to a hospital in Bangui.

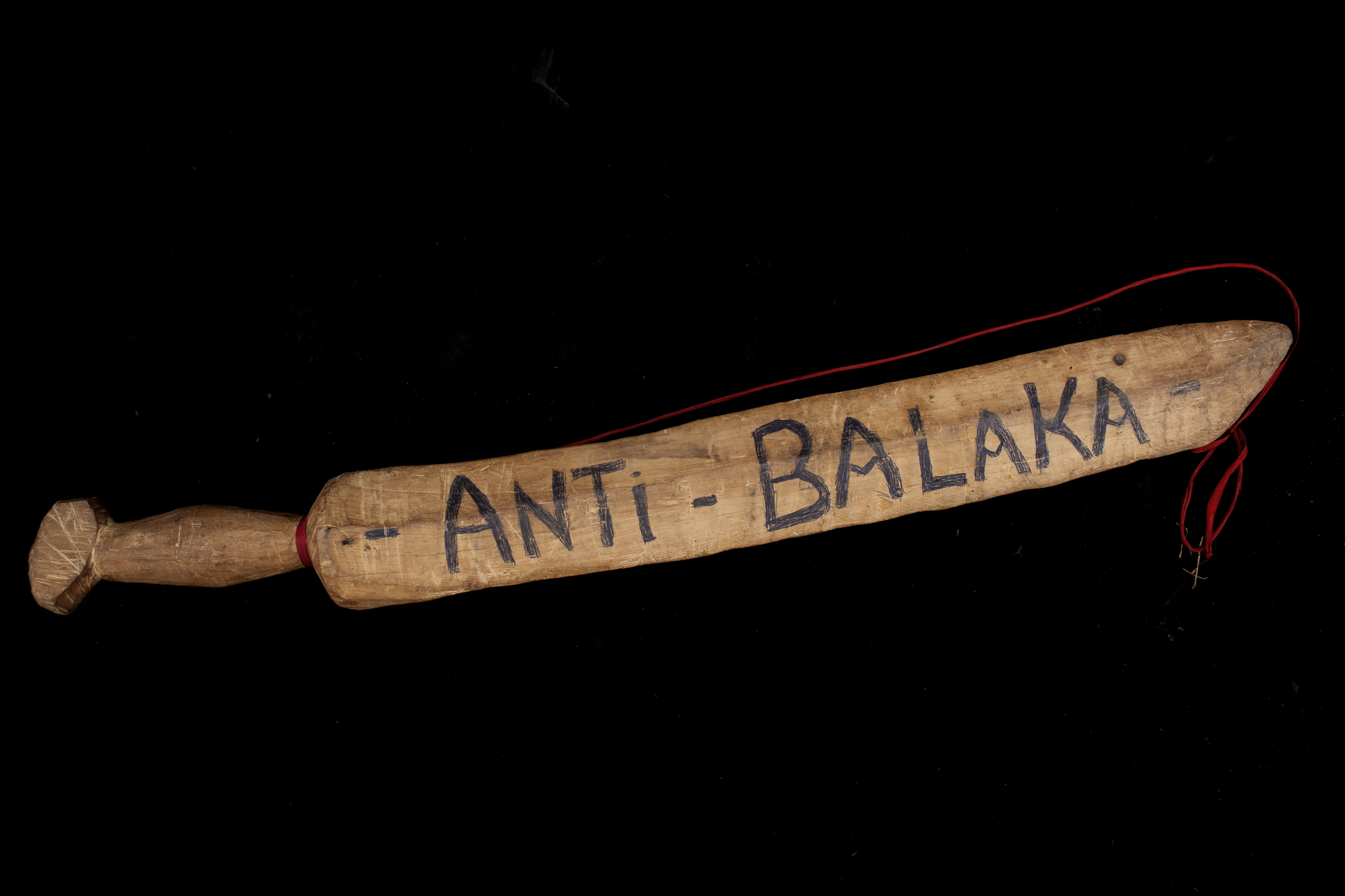

When a Muslim dies in Bangui, the body is brought to the Ali Babolo mosque. Imam Yaya Wazziri, 72, washes the body and prepares it for burial. But currently, it's too dangerous for him to accompany it to the Muslim cemetery. He tried asking African peacekeeping troops for an escort, but the vehicle was attacked on the way back from the cemetery. “So we said, ‘We need people who are stronger,” Wazziri said. The imam then called on French forces, who would accompany the mosque’s vehicles only as far as a checkpoint at the city’s northern limit. “Well, the anti-balaka were on the other side of the barrier, scraping their machetes on the pavement and saying, ‘Come, come, come, thank you, today we have lots of meat,’” Wazziri said. So Wazziri appealed to the Red Cross, whose workers now collect and bury the bodies brought to the mosque – numbering in the hundreds since violence against Muslims escalated. “The way they were killed,” he shuddered. “You have ones with slit throats, beheaded, ripped stomachs, the genitals …” His voice trailed away. He said he tries to preach patience. “But you know,” he said, “young, out-of–control people, there is no shortage of them in life. When they see the way their parents were killed, they too go looking for revenge.”

Radia Abdel Aziz, 28, had a good life with her husband, Mahamat, who owned his own auto repair shop. Now she spends her days sitting under a mango tree at the Central Mosque in PK5, looking at old photographs. Earlier, anti-balaka fighters burst into her home and opened fire as her husband was saying midday prayers. They shot him three times, she said. He tried to run, but his attackers cut him with machetes until he died. She fled to the mosque with other family members. “We sleep on mats on the ground,” she said. “When it rains, we all run into the mosque and stand there waiting for the rain to stop. Then we go back out to sleep.”

Ousmane Moussa, 54, brought his family to PK12 because he thought they would be safe there. But the Muslims packed into less than one-square mile around a mosque were surrounded by hostile Christians who fired guns and grenades at them. Two of Moussa’s cousins were shot in the legs outside the mosque where they slept. Moussa wanted to leave, but said he was trapped. His 27-year-old son, Adan, tried to drive to the southern city of Bambari, where he had heard that Christians and Muslims weren’t fighting. But attackers fired at the car and killed him. Moussa was hoping the peacekeepers would evacuate him. He’d go anywhere, he said. “Anywhere but here.”

Ibrahim Djouma, 42, right, a mechanic, lost most of his family on the December day that anti-balaka forces launched a major assault on Bangui. His mother and two older brothers were shot and killed. As Djouma ran, he came face-to-face with a militiaman who shot him in the knee. Red Cross workers found him the next day and brought him to a hospital. That’s where he was reunited with his 9-year-old son, Aroune, left, who was saved by a neighbor. He does not know what happened to his wife and two other boys. They fled and have not been seen since. “I just want to get out,” he said.